Arch

443/646: Architecture and Film

Winter 2014

Woman in the Dunes (1964)

|

Arch

443/646: Architecture and Film Woman in the Dunes (1964) |

|

Discussion Questions:

Remember, your images are ABOVE your name.

Please answer the questions below. Use paragraph form. Submit to LEARN. THINGS TO KEEP IN MIND WHEN ANSWERING THESE QUESTIONS: I am looking for general observations about the film and the relationship to any aspect of f/x that we have examined. Although the questions are specific to Woman in the Dunes, feel free to reference any of the other movies that we have seen this term or that you think might be appropriate. |

x |

|||||

| 1. | |||||

Hillary Chang In "Woman in the Dunes", I felt that the directors choice to shoot this film in black and white instead of colour was a very artistic choice; the black and white highlighted the forms of the sand and the bleakness of the characters' situation. I wasn't able to watch the whole film, but from the parts that I watched, shooting this film in colour wouldn't have added a significant amount of new information which would have improved the narrative or enhance the visual effect of the sand. In black and white, the sand became a key texture and prop which guided the narrative and affected the characters, but if it were colour the symbols attached to sand (the familiarity of sand's warm yellow, dry desert or sunny beaches) the viewer would have a biased opinion instead of being convinced by the director's interpretation of the oppressive nature of sand. Black and white also put more focus on the lighting choices the director made, from the blinding outdoor "daylight" to the dimness and extended shadows created from interior shots. |

|||||

| 2. |  |

|

|

||

Patrick Cheung

|

|||||

| 3. |  |

|

|

||

Wesley Chu As Teshigahara’s Woman in the Dunes is an allegorical piece about the struggles of life and the existential futility of our advancements as a race, the use of insects is a very important metaphor. Upon Niki’s arrival in the dunes, there are several macro close-up shots of insects in tubes and jars for his collection. There is a foreshadowing here of his impending situation, as he himself is about to be trapped into a meaningless struggle for his own existence. An insect placed in a glass tube has no idea where it is or what it’s being taken for, or even the fact that it’s being taken. Before it was collected, it probably had no idea what it was doing on this earth anyway. We as people like to think that there is a purpose to our existence, but ultimately it is a question that has never (and perhaps will never) have an answer. Niki holds on to his previous life as an educator and scholar, despite being in a situation where none of this will ever be useful. “could we at least have a radio? So we can keep up with the news”, Niki says to his captor and partner, but even he quickly realizes the futility of knowing what is going on with the rest of the world. Given that we normally analyze, inspect, research, and study other creatures in such a scholarly fashion, author and screenwriter Kobo Abe and Teshigahara beg us to look at our lives through this same lens and question it the same way. Concerning the macro close-up shots of the insects themselves, I think it is hard to appreciate this type of photography from the audience’s perspective, especially at this given time. In 1964, the technical limitations of optics and image capture was much more restricting. Standard photographic filmmaking equipment did not allow for anything close to a 1:1 magnification capability outside of scientific lab equipment. This meant that cinematographer Hiroshi Segawa and Teshigahara invested a lot of effort to figuring out how to photograph sand and insects in such a way, which brought impressive results for the film.

|

|||||

| x | 4. |  |

|

|

x |

Charlie Gao

|

|||||

5. |

|

|

|

||

Maighdlyn Hadley

|

|||||

| 6. |  |

|

|

||

Kyle Jensen

The point of view of these high shots is symbolic of the captors who control the trapped characters. The trapped house was filmed almost like a doll house with people who can be manipulated when required, and who also need the assistance from the villagers who have power to keep the prisoners alive. The captors also have full view of the captured citizens and often abuse their power. The abuse can be seen when the villagers tempt the entrapped couple with temporary freedom in exchange for a publicly witnessed sexual encounter. This overbearing attitude from the captors can be felt through views showing how low and vulnerable the two trapped souls are as the mob of villagers glares down at them with wicked-looking masks. In this case the shot is from the perspective a of the prisoners is also captured, and shows the opposite feelings of intimidation and helplessness, but the effect is just as important in the emotions of the film. Furthermore, the scale of the sinkhole is seen best by viewing it from the top as the harsh shadows cast into the hole itself show the depth of the house and emphasize how difficult it would be to escape from its confinement. The movement of the sand as it collects around the house gives the viewer an understanding of the full scale of the house compared to the collapsing banks of sand. The camera position looking into the hole seems to dwarf the inhabitants as well as their shelter and shows the shabby construction of the accommodations. One clearly appreciates the utter disregard for human comfort, the appalling living conditions, and the suffering of the inhabitants as they are forced to deal with the harsh environment of the sand. It is possible to make a clear comparison between this situation and the insects that are filmed in the earlier section of the movie. The insects were always filmed from above, much like the point of view looking into the pit, a similarity that seems to show that humans are still only creatures in nature who must struggle to survive in a hostile environment. This relationship was further emphasized by the interesting fact that the main character was in that location in order to capture such insects for his own collection. His fate now mirrors that of the insects he was formerly pursuing. Overhead shots also help the viewer understand the relationship between the two strangers. In the beginning of the film the body language can be seen as hostile and uncaring as the newly captured man takes out his anger on the woman, making her a captor in the hope of negotiating his freedom. A shot showing the woman bound on the floor and the man sprawled out in exhaustion again helps illustrate the hopeless confinement of the characters. As the movie progresses they except the fact that they are trapped together and eventually embrace the roles of man and wife. The viewers are offered a first hand look at the inner confines of this “home” and how the characters function on their own to bond and eventually come to grips with the inescapable situation they are faced with. Understanding camera views and there effects on emotional aspects of the subject references- |

|||||

| 7. |  |

|

|

||

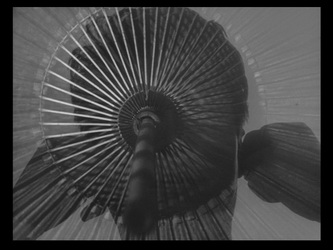

Dan Kwak Teshigahara uses superposition as means of translation and transition by merging two different scenes of mutual opacity. It creates a peculiar, symbolic representation while it also performs as an easy transition of the narrative. The most memorable scene is the man’s waking to be diffused with the image of the underneath shape of the umbrella. The effect of black and white, thereby the clear distinction between light and shadow, resonates a powerful imagery of little sticks of the umbrella in a rotational motion like some sort of a dazzling dream. This is especially emphasized with the appearance of a sudden, sharp sound of Japanese instrumental. Its monotonic imagery is, in fact, only explainable for a symbolic importance, which is rather vague and unknown. The other scenes of superposition are also vague and dreamy without a specific, defined purpose to a certain destination of the narrative. All of them always transit the man’s emotion to his thought to the action. The director used this technique for various purposes: to stitch the man’s emotional state to his thoughts, to literally move the narrative and to convey a symbolic message through a powerful imagery. I personally remember this technique of superposition in other older films being used as simply a natural transition. It is the easiest and the most natural, classic method of transitioning from one scene to the next by means of dissolving and resolving. Another film that used superposition intently was Alphaville, where the use of superposition was not transitional but translational – as representing an imagery upon the natural scene as a symbolic addictive. For example, an image of an abstract object was superposed on the narration of the voice-technology’s imposition. However, Teshigahara seemingly employed the superposition to accentuate the advantage of black and white at best to compose as many purposes as possible. This, overall, adds a further layer of complexity and the magical essence of mystery on the narrative. The beauty of the film, in fact, seems to lie in this complexity portrayed by the composition of simple, powerful imageries. The image of a sand dune is no more than mountains of sand. However, it is this eerie and rather complex narrative that audience is caught on, which Teshigahara constantly engages by his techniques such as superposition. Furthermore, the humble palette of objects enable him the power to establish a greater, multi-dimensional abstraction. And traditionally, Japanese culture seemingly embraces this form of abstraction quite powerfully. This shows in Teshigahara’s use of superposition upon the simple and abstract form of the narrative. For this reason, the use of superposition seems to validate for more than one purpose but many in The Woman in the Dunes. As to the question of its expiry of the technique, so long as a technique fulfills its need specific to the director’s intention; as it does so in Tehsigahara’s case, it is valid and current.

|

|||||

| 8. |  |

|

|

||

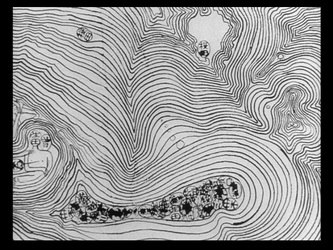

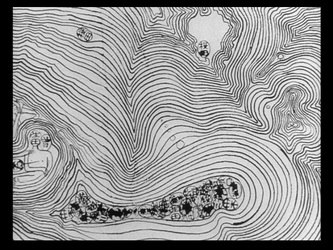

Milos Mladenovic Being a film shot entirely in black and white, the role of other effects, such as shadows, is immediately taken more seriously (i.e., the removal of color and the resulting polarization of the film into shades of white or black heightens the degree of influence of every other aspect of the film on the film itself). As such, the shadows play an important role in this film, particularly in helping to delineate space and orient the viewer within many of the seemingly ambiguous settings of the film. The sandscapes that provide the setting for the film almost create a sense of a space that is characterized by formlessness and ambiguity. The shadows, such as in the first and third stills above, allow for an accurate perception of space, proportion, and shape amid such enigmatic surroundings. In these two stills, especially, the role of shadows is important in that it also allows for a temporal and sensual experience of the scenes depicted. Harsh shadows on the sand and the man's back allow the film to transmit, medially, the sensual experience of being in a desert in which you are incredibly hot, thirsty, and in solitude. Coupled with the strategic placement of the camera behind the man's back in many cases, where one feels as though s/he is directly within the scene, the effect is further enhanced. With the removal of color, which is normally the most straightforward means by which this type of sensual experience is captured and conveyed medially, the shadows in the film are used as an essential effect in lieu of any such color. Thinking about it retrospectively, the film would likely not be as powerful emotionally and sensually for the viewer had the experience of being trapped in a scorching, arid, ruthless desert setting been communicated. Additionally, the interplay of interior and exterior shadows throughout the film nod towards this antagonism between the enigmatic, formless exterior (sand) surfaces and the more well-defined, geometric interior surfaces and spaces. In each, the shadows help transmit an experience medially (secondarily, by means of the moving image as opposed to the actual firsthand experience) but also reveal depth, dimension, and a sense of the scale of the places and objects being seen. The shadows unite the contrasting characteristics of the interior human environments and the exterior untamed ones by helping "tame" them in a way, and also enriching this interplay between a sense of ambiguity or dreamlike catharsis in the film with one of sharpness and clarity.

|

|||||

| 9. | |||||

Arturo Rivera After watching the Woman in the Dunes for the second time, it became apparent that the director intended this to be a film about sensations, about creating a certain mood that could resonate with the viewer through the use of very specific techniques. We discussed in class the fact that the decision to make this a black and white film allowed the viewer to focus on textures and touch, and while the camera angles and positions certainly contributed to the overall mood of the scenes, I believe that the soundtrack, or lack thereof, is what really sets the atmosphere on the film, as well as providing depth to the narrative and the disturbing sense of isolation that the director wanted to portray. The interesting part of the soundtrack is that it is mostly composed of soundscapes and very few and short musical sections, since the dialogues between the actors present the mood of the film. In the exterior scenes the wind is clearly the prevailing source of sound, with the casual interaction with more tangible elements, such as ropes, fabric and wood planks. The interior scenes rely mostly on the interaction between the protagonists and the sound of the common household items that they use. It is only at the moments of tension that the soundtrack becomes harsh and unnerving, with metallic strummings and chimes, as to set the mood according to the emotional distress that the characters are dealing with. It is only in one scene when the villagers gather around the pit to force Junpei to rape the woman that we get a sort of aboriginal musical score comprised of tribal drumming patterns and voices. I also believe that the silent characteristic of this film is what allows it to feel more real and it is what ultimately delivers the message in a more powerful manner. It is possible then, to make a fair comparison between this film and Playtime, since Tati also relies heavily on the used of background noise as the musical score to provide the mood for the film. The difference between these films has to do with the fact that in Playtime there are no discernible main characters and that the transition between their dialogues and the background noise is softer and more gradual, whereas in The Woman in the Dunes is more abrupt. In conclusion, it is fair to say that The Woman in the Dunes manages to position the viewer in the shoes of the main character, Junpei, by allowing us to see what he’s seeing and to feel what he’s feeling, through the use visuals and the soundscapes, while the musical score provides the disturbing atmosphere of the film. ¹ IMDb: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0058625/

|

|||||

| 10. |  |

|

|

||

Morgan O'Reilly The extreme close-ups of the human form exemplified in these stills are used by Teshigahara to manipulate the viewer’s sense of scale. Between these close-ups and wide shots of the undulating sand dunes, the result is an abstraction that blurs differentiation between the prisoner’s bodies and the sandy landscape that traps them. Unity is created between the characters and their environment. This abstraction puts emphasis on the intensity of the situation in which they find themselves and the degree to which they are confined by the landscape. Furthering this concept in terms of the relationship between Junpei and the woman in the dunes, close ups have been used to specifically make the woman part of the extraordinary landscape. In normal close up shots, special attention is given to her naked form and its contours. Crossfades between the rippling sand and her bare body very effectively create a relationship between the two. Her body and the landscape merge to become synonymous and to have the same seductive quality that has lured Junpei into this prison. The film’s tone gradually becomes sexually charged. She has trapped Junpei just as much as the physical confines of the sinkhole have. As this sexual tension in the film lingers, the extreme close ups take on an erotic quality. Every touch resonates in this small world that Teshigahara has created amidst the sand. A review of the ‘The Woman in The Dunes’ in the Torontoist, aptly states “He (Teshigahara) pivots between medium shots of the couple growing closer in their claustrophobic setting and extreme close-ups of their sand-blasted flesh that are both erotic and grotesque…” The abstraction that is created by these macro shots of the body are sensual, but also full of terror as they allude to the greater landscape that traps the couple. As Junpei becomes physically involved with the woman, it is as though he is sinking deeper into this trap, which in these moments of lust is revealed by the extreme close ups. The extreme close ups also assist in emphasizing the invasive presence of sand. The abnormally close shots of the characters’ bodies lead the viewer to focus on things which might not normally draw attention. The viewer is shown the characters’ skin, their pores and wrinkles, their hair, the gathering of sweat and soap. As a result the tactility of the film is incredibly heightened. All of these shots are punctuated by grains of sand. Its relentless presence drives the viewer to the point that the discomfort of being forever sandy is felt. The sand is inescapable and can never be completely washed it away. One of the most memorable of these close ups is that of the woman’s eye, as featured in the first still. While this focus on the eye supports the understanding of this woman as a terrifying seductress, it also adds to her mystery. The eyes are the natural place one looks to understand the inner workings of a person. The woman of the dunes’ eyes however, betray little emotion in these close ups. This absence of emotion is provocative as it leaves one to wonder what she is feeling and thinking as well as how she came to be in this place. Is she simply resigned to her fate in this pit or does she know of nothing more and therefore cannot be disturbed by it? Richard Gray. ‘Mise-en-Screen: ‘Woman of the Dunes’. http://www.atthecinema.net/mise-en-screen-woman-of-the-dunes, 2011. Angelo Muredda. The Woman in the Dunes. http://torontoist.com/2013/02/the-woman-in-the-dunes/, 2013. Bibliography Scott Gray. Woman in the Dunes. http://exclaim.ca/Reviews/TIFFRetrospective/woman_in_dunes-directed_by_hiroshi_teshigahara, 2013. Roger Ebert. Woman in the Dunes. http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-woman-in-the-dunes-1964, 1998.

|

|||||

| 11. |  |

|

|

||

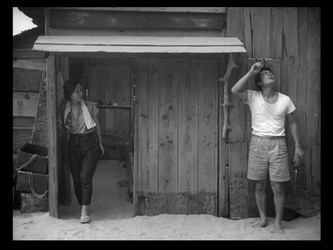

Patrick Rossiter In Woman in the Dunes, the viewer has the chance to slowly be immersed into a world that is not all that it seems. From the beginning, we are led to believe that there is nothing overly unusual about the geography and community that the main character, Junpei, is exploring. Soon after being invited to stay the night, after missing the last bus out of the village, it becomes abundantly clear that things are indeed stacked against the main character. He is trapped and his hostess is no more than bait for bringing in someone else. After being lowered into the pit and introduced to his hostess, we begin to see the living quarters and its position in the sandy landscape. The imagery used rarely gives a wide angle shot of everything, but glimpses here and there of the layout these characters are living in. The black and white film technique allows for the wooden shack to blend in with the sandy environment. Filmed in high-contrast monochrome with large portions of the screen plunged into complete darkness, each shot is formally composed often to the point of pure abstraction.i The line between inside and outside is blurred by this and really we are only left with the wooden elements and the sand textures to make obvious where one begins and the other ends. During the film, the dwelling is shown to the viewer as entirely inadequate for its environment. It does provide basic shelter from the wind, sun, rain, and other weather but it is designed very poorly to keep the sand out. So much so it may drive an architecture student mad just watching how permeable the floors, walls, and roof are. As we see that special care is taken to deal with the sand being a constant nuisance to the interior life of the shack, the viewer can only feel the uncomfortable sand ridden existence that the prisoners must endure. The use of the “screen” within this context is an excellent way of describing the story to the viewer. In my opinion, there are three aspects in which the use of the “screen” communicates deeper meanings within the story. 1 – Communicates that it is a prison. With the vertical lines and spacing identical to a set of prison bars, the viewer sees this world as though they are locked in it. This imagery is synonymous with the concepts of being locked up and held against one’s own will. As the viewer, it is very effective in creating an unwanted and disturbing effect and we are forced to perceive the point of view of the prisoners as our own. 2 – Communicates that the dwelling is forever at the mercy of the sand. We understand very soon into the film that the house is at the mercy of the sand dunes or drifts. The trapped woman explains that "the house will get buried. If we get buried, the house next door is in danger.”ii We can see that the house is not only in danger of being buried because of the constant changes in the surrounding landscape, but we also see that house as deeply flawed. It is poorly suited for its location. The sand is constantly coming in on the best of days and on the worst it little more than a wind breaker. The “screen” shows the viewer this, there is little barrier from inside to outside and we know this without thinking about it. 3 – Communicates the spatial relationship between inside and outside and the blurred threshold between these two places. The overhead shot of the pit and the shack offer the viewer an understanding of the environment the prisoners are trapped in. The use of the “screen” allows for a greater understanding of the spatial relationship between the walls of the shack and the walls of sand outside of them. We are able to develop a map or plan of the spaces and the relationships they have with the local environment. The “screen” offers us a semi-transparent view of this, we see what the characters may see and we may experience what they may feel. The sand appears to be a carpet which extends from the outside to the inside. We would not truly know this without the shots through the “screen”, often it is hard to discern if we are looking outside or in. I would compare the use of the “screen” in this film a similar technique and effect in “Playtime” – the “screen” was not used so much as the viewer was placed in a position to feel as though they were on the outside looking into a scene or vice versa. The scene in the restaurant allowed the viewer to see what was happening from many angles – being inside and then outside looking through the windows street-side. i “Woman in the Dunes: Existential at its Disturbing Best,” last modified January 8th, 2012, http://lisathatcher.wordpress.com/2012/01/08/woman-of-the-dunes-existentialism-at-its-disturbing-best/. ii “Woman in the Dunes,” last modified February 1st, 1998, http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-woman-in-the-dunes-1964.

|

|||||

| 12. |  |

|

|

||

Simone Tchonova There are a range of types of depth of field. Essentially, every shot uses some amount of depth of field, the one extreme is called a long depth of field meaning that most of the scene is in focus whereas the other extreme is shallow depth of field and there is only a fraction of the scene in focus. When the shallow depth of field is used, the viewers eye is brought to focus on the object which is sharp and clear. There are many times where the sand(dune) is depicted either the main focus or the blur in the background. One example of when the sand grains are in complete focus is when the lost man finds a bug inside of the sand and picks it out with his fingers. Here, the director wanted us to pay specific attention to the detail within the grains of sand. This is a close of example of the use of depth of field. Another example, which also focuses in on the sand is when the main character is walking through the dunes in the afternoon heat. His body motion is blurred whilst the vastness of the sandy landscape is emphasized in its sharpness. In my opinion the use of depth of field in relation to the sand is always to focus on the sand and away from the moving object. In typical filmmaking the object in motion is seen to be in greater focus. In both methods, it is this filmmaking strategy that is used to highlight certain aspects of the story. The director must have thought it provocative to focus in on the landscape and surrounding environment ; as it is a pivotal aspect to the impending result of the plot where the man is better off to remain in the dunes than to journey back to where he came from. Relating back to the initial question in differentiating between the usage of depth of field interior versus exterior ; the interior views use a greater blur effect in the architectural surroundings than the exterior landscape. For example the interior scenes are shot to be more intimate and affectionate scenes between the woman and the man. There are times when either the woman is in clear focus while speaking or the man or neither are in focus and a conversation is being carried between them two. Below is an example of interior architectural materiality being emphasized as the characters are having an intimate discussion. It is the grain of the wood that our eyes want to focus on. In many scenarios wood symbolizes warmth, and comfort. The use of depth of field in the film creates the atmospheric relation between the humans and their surroundings of their material settings of the film. Be it a cozy interior or a vast, spacious landscape.

|

|||||

| 13. |  |

|

|

||

Yiming Wang

|

|||||

| 14. |  |

|

|

||

Victor Zagabe The sand is used as a cinematic device to bring some sort of scale into the story. Its overabundance, causes the protagonist to appear to be but a simple ant among the large terrain. This is seen evidently as we watch the protagonist try to climb out of the dunes. The sand is also used as a dissolve transition from one scene to another. Its used\ as the fade in texture is meant to, once again, show its predominance in the surroundings. Ultimately, these effects reflect the fact the idea that given the surroundings, sand is all one can think of while in the dunes. It becomes an obsessive desire to come to know it. It is very easy to see sand as a character in the film, it acts as a dividing wall, guarding the protagonist in the depths of its dunes. Something that makes the sand more character like is its ability to be manipulated and altered, depending on the conditions given. Its formation is very organic due to its influence by wind, water, and sun. In this struggle between man and nature, the protagonist learn various ways that sand can help him survive his stay in the dunes. He comes to the realization that it is not within the nature of the sand to allow him to escape on his own, but does however, discover that it may allow him to bring some sustenance and prosperity into his life, through the preservation and filtering of rainwater. The sand is used a cinematic devide that plays with light, depth, and the perception of objects. You see this in the way that it reveals the location of water, and human circulation. The shots taken from an areal view allow for a deeper understanding of the overabundance of this particular character.

|

|||||

updated 25-Apr-2014 9:28 AM